We are Cheetah Friendly – Part I

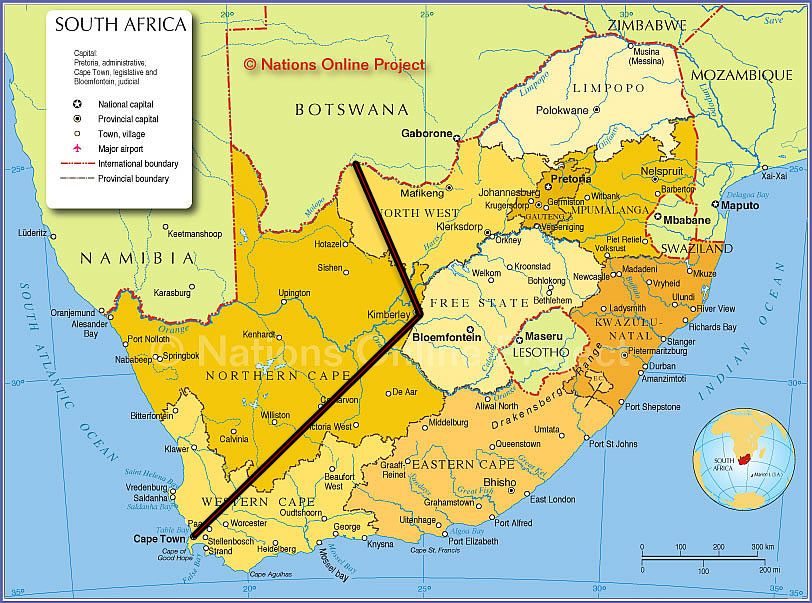

My journey from Cape Town to Kimberly by plane, then on the road to the border of Botswana in the NW Province

“Howzit? How are the cheetahs?” ask my new friends in Cape Town. “I’m going to Bray for a few days.” “Where??” When even a South African hasn’t heard of this place, I know I’m in for another adventure. Bray is a frontier post located 200 meters from the border of Botswana in the Southern Kalahari, the North-West Province of South Africa. There are an estimated 500-800 free ranging cheetah in the country, many of them residing in this area which is also populated by a large number of commercial livestock, game and hunting farms. For generations cheetah and other predators have been killed in the name of protecting livestock, but there is a solution where both humans and predators can co-exist.

Filled to the rafters with dog food, Cyril prepares to deliver to over 11 farms in the NW Province, South Africa

I flew into Kimberley to meet Cyril Stannard, Anatolian Project Coordinator for Cheetah Outreach. Cyril is driving a large pickup (bakkie as they’re called in Africa) filled to the rafters with dog food leaving just enough space for an empty animal crate. This crate won’t stay empty for long. Cyril implements Cheetah Outreach’s privately funded Livestock Guarding Dog Program (LGD for short), delivering Anatolian Shepherd puppies to farms willing to participate in a program of non-lethal predator management. In short, this means co-existing with the cheetah. The puppies are donated and provided food for one year, then the farmer takes over the costs.

The Livestock Guardian

The Anatolian Shepherd is a known as one of the best guard dogs on the planet. A Turkish breed that goes back thousands of years, the Anatolian does not herd livestock like a Border Collie or other sheepdog, but rather stands its ground with their ‘family’ against any predator that threatens them. Cheetah Conservation Fund, Cheetah Outreach and Cheetah Conservation Botswana are among the many NGOs that offer LGDs to farmers, and their popularity is growing not only in Africa but in the Western United States as well.

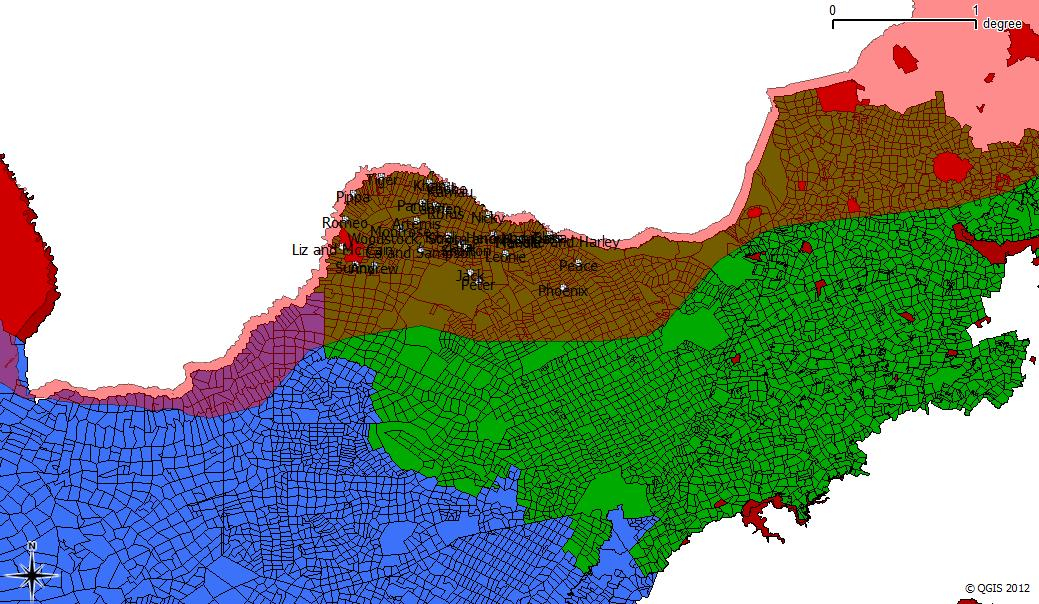

Cyril’s job is a life on the road. He visits all the farms who have dogs from the program and checks on their progress, drops off food, and talks with the farmers about successes and pitfalls. This truck has seen a lot of dusty roads in the Kalahari. Farms are huge properties spread far from each other. Not everyone in this region has joined Cheetah Outreach’s LGD program. One glance at the map and its easy to see the participating farms are a drop in the bucket, but a hopeful one where neighbors can influence neighbors. Who wouldn’t want to share success and money-saving management tactics?

The intricate outlines delineate hundreds of privately owned farms in the NW Province where Cheetah Outreach has placed LGDs. The smattering of dots and names in black on the map near the top are the farms participating in the program. Many more are needed to create corridors for the cheetah to safely roam without possibility of being shot.

Curiously gazing out of the crate after a long drive

Just outside Kimberly we meet up with commercial breeder Hannelie Liebenberg to receive three Anatolian Shepherd puppies just seven weeks old. The over-the-top cute dogs are born in what is called supportive conditions. The mother gives birth in an enclosure with sheep or goats, and the dogs are raised with livestock. At seven weeks these little fluffballs are ready to bond with their flock for life. They’ll grow to nearly 130lbs and view their flock as their family, guarding against predators day and night. For now it is hard to remain professional and not squeal over the little guys.

A game of chase before the long drive north

Back on the road, with puppies in the crate barking loudly, we make another stop at a grocery during the long drive to Bray. Panicked word from the Tapama Lodge which will be our home base for the week, is that visiting workmen, malarial sprayers, are devouring all the lodge’s food. Being so remote, replenishing supplies is no small matter so we pick up loaves of bread and other items for their kitchen.

This is truly one of the more isolated parts of the country. There are no daily newspapers and scant cell phone coverage. Free ranging cattle peruse the dusty road in front of Bray’s only gas station. While Cyril fills the tank in preparation of hundreds of miles of driving per day, I find amusement watching a dung beetle roll its bit of you-know-what around the pump.

Our first stop in the area is a visit Piet Theunesin’s farm. The Theunesins are taking in one of the puppies we’ve brought from Kimberley. Over a cup of coffee, Piet signs the LGD Program Contract agreeing to care for the dog and practice non-lethal predator control, then its time for the puppy to meet his new family.

The puppy’s first encounter with its new flock of sheep is a little awkward.

The little dog is carried into a yard with a group of curious sheep. He trembles and looks very confused. Stumbling about as we all stand back, he turns in circles and tries to return to the safety of the humans. One can only imagine the weird upheaval of the last 36 hours for this pup. Taken from one family, bouncing about in a truck with his brothers and now in a strange land with a very large sheep looming near him, he has no choice but to be courageous. The Theunesins give him a few minutes with the sheep as a first encounter.

Cyril Stannard of Cheetah Outreach delivers an Anatolian Shepherd to its new home

It will take a little time before all the animals are accustomed to each other. Accepting a puppy is a commitment to training. Within one year the dog will have paid for itself in livestock saved from predation in this wild landscape, but it takes work. The process is not as easy as dropping a puppy into a kraal (fenced enclosure). The Southern Kalahari region is a harsh environment. In rare instances, a dog’s personality won’t be suited for the work, or worse, it may fall prey to snakes, illness or accident. When this occurs, the farmer more often than not chooses to try again and requests another dog, a testament to the efficacy of the program.

The numbers don’t lie: Once farmers take on the cost of maintaining their dogs, feeding expenses range from $450 – $1,600 per year. To cover the bottom end of this range, a dog must save four lambs, three goat kids, or one calf in a year. The cost of top end feeding is 12 lambs, 10 goat kids, or 3 calves. Since 2005, Cheetah Outreach has placed 125 LDGs. Over that period, livestock loss due to predation on participating farms has been reduced by 95 to 100 percent.

PERC: Cheetah Conservation: How Dogs are Saving Cats in South Africa by Emily Wood & Annie Beckhelling

You read that right, one hundred percent.

Stay tuned for Part Two where we drive through one of South Africa’s half-abandoned ghost towns, still populated by military families, more puppies meet their flocks, and a farmer’s love for his dogs is challenged by the elements.

Maps provided courtesy of Cheetah Outreach

0 Comments